platform_as_a_curatorial_research_lab_for_independent_curators

Ibanjiha is an iconic queer artist in South Korea. They are iconic not only because they are one of the most well-known queer artists in South Korea today but because they have survived more than a decade as a queer artist. When they debuted in 2004, there were many other drag queen and king artists, queer musicians and filmmakers; however, many disappeared from the scene, while Ibanjiha remained, struggling to become legible not only in the LGBTQ+ community but in the contemporary art scene at large. They used multiple names besides Ibanjiha – Soyoon Kim, Somurai and Sopal – and multiple mediums including performance, painting, animation, and film, in order to navigate spaces that were unwelcoming, if not downright hostile, to queer artists. The name Ibanjiha is a combination of two words: Iban (queer) and banjiha (half-basement). The name highlights the harsh living conditions endured by the queer artist, as well as the lack of infrastructure provided by Korean society for the development of their work. Ibanjiha spent long years in a basement apartment and was literally an underground artist until their work suddenly reached a wider range of audiences, readers, and spectators in 2019-2020. With the live show entitled “Ibanjiha’s Very First and Last Human Rights Solo Concert” in December 2019, their work just managed to cross the threshold into mainstream popularity and attract more attention from both the LGBTQ+ community and popular media, including Podcast shows and publishers. With this abrupt shift, Ibanjiha’s work began to circulate in major institutional spaces, including museums and galleries, major publishing houses, North American and European art schools and universities.

It was on a snowy day, December 21, 2022, that Ibanjiha offered Bu-chi-ui Ja-Gung (Butch Palace for the Son) , an audience-participatory-workshop, as part of the year-long Korea-Netherlands International Arts Joint Fund Programme. In her opening remarks, Mok Honggyun, the director of the programme, introduced Ibanjiha’s project through the theme for 2022– tolerance and innovation—and invited the audience to reflect on how the project contributes to the diversity and inclusiveness of the art world.

The title for Ibanjiha’s workshop, Bu-chi-ui Ja-Gung (Butch Palace for the Son), originates from a report that the artist published in July 20221. Ibanjiha expanded the literary piece into a live performance event, in which the audience was invited to collectively imagine what a bu-chi’s uterus is and does2. Bu-chi is a Korean vernacular term originating from the English word butch, which has been circulating in the Korean LGBTQ+ community since the 1990s. The Korean word ja-gung is commonly translated as uterus; however, etymologically, ja means son and gung means palace, forming the compound phrase palace for the son. Thus ja-gung, or uterus, is already embedded in a patriarchal context, which reductively assigns the female reproductive organ the purpose of produce sons. The female body is subordinated to the social function of producing male heirs to sustain patriarchal kinship structures. Ibanjiha’s gambit might be articulated thusly: What would happen if we focus the spotlight on this particular organ, with all of its cultural baggage, from a queer point of view?

After opening the workshop, Ibanjiha walked to the front of the room in the exaggerated manner of an instructor. Firstly, they wrote the Korean title of the event on the whiteboard: 부치의 자궁. “These are the two key words for today’s lecture: bu-chi and ja-gung,” Ibanjiha explained, “Our goal today will be to reflect upon the butch’s uterus and attempt to sculpt it ourselves. I will then make an assessment of your work and offer feedback.” Ibanjiha initiated a discussion by asking everyone about the meaning of the word bu-chi. After a pause, audience members began offering answers: a person whose hair is short, a person who does not live the life society dictates, a person who truly loves women. “If you look up the English term butch in the English-Korean dictionary,” Ibanjiha intervened, “It says butch refers to a woman who acts like a man. […] So the outer aspect of bu-chi is male, but the inside is female, and in the uterus there is a place for the son.” Even if we imagine that the term bu-chi refers to a person who is gender non-conforming, Ibanjiha implied that the bu-chi would be called back to the body by the name of the organ that is defined as a “palace for the son.” Ibanjiha asked the audience members to confront this paradox as they prepared to physically shape their own version of a butch uterus using clay provided by the workshop.

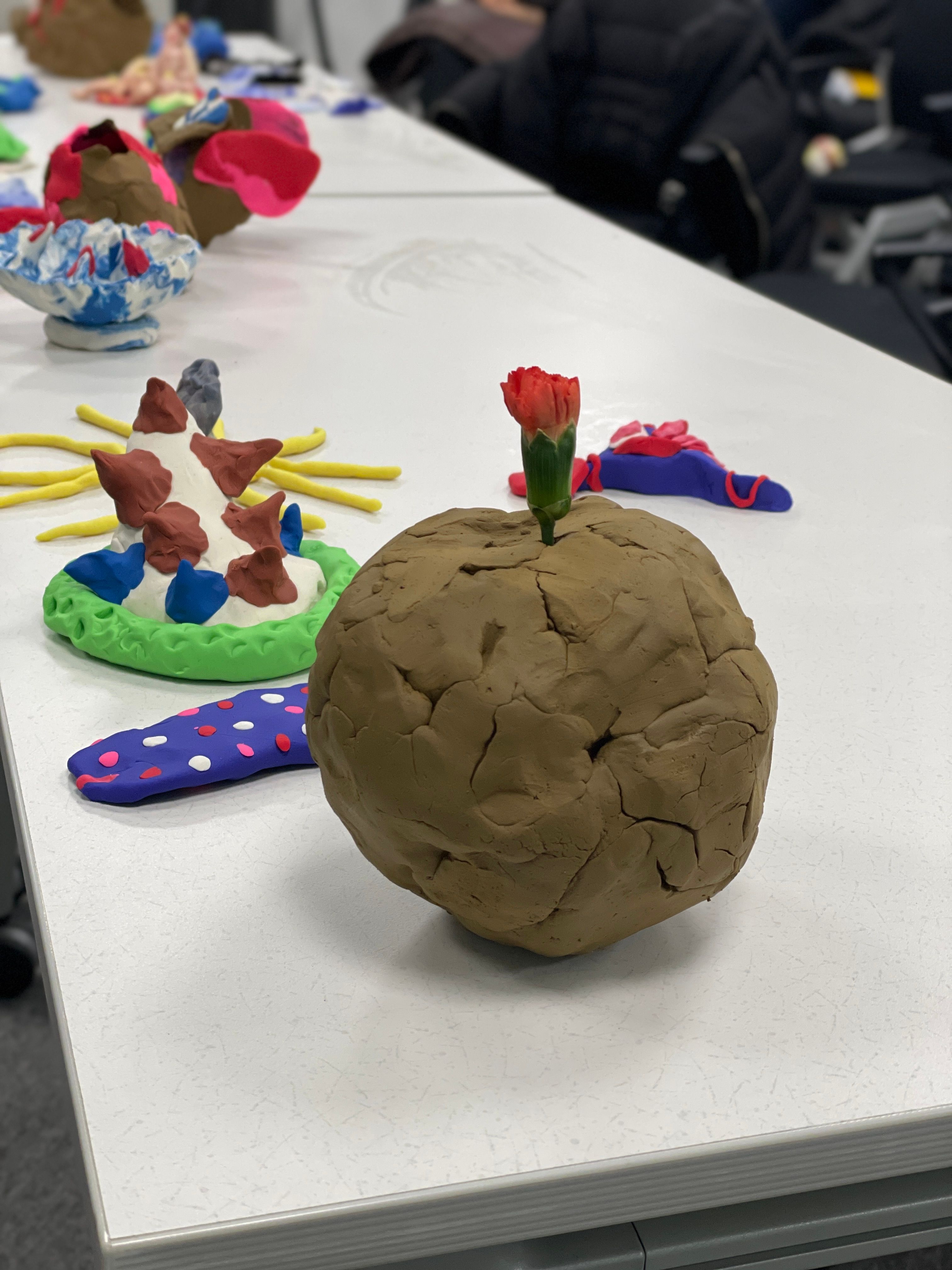

After several minutes of group meditation on the notion of a butch uterus, Ibanjiha passed out lumps of clay in various colors. Parodying the soothing tones of a meditation guide, Ibanjiha intoned: “We all came here with different ideas [about what a butch uterus is]. Some people clearly know what bu-chi means; others might want to turn away from bu-chi; and a few may have just come here to watch weird people doing weird things together. I’ll tolerate everyone and offer this innovation. Express whatever comes to your mind. You are not wrong. What you are doing now is right. I will cheer you on today.” Led by Ibanjiha, audience members sculpted their own versions of a butch uterus in clay and placed them at the front of the room to be viewed by everyone else. Butch uteruses came in all kinds of shapes and sizes.

Ibanjiha began a critique of the many pieces displayed on the table. They picked up one piece and asked who had made it. An audience member walked over to Ibanjiha and handed them her cellphone, in which she had typed some thoughts about the butch uterus. Ibanjiha read out loud from the phone: “Bu-chi was born from the soil. Uterus is a part of woman but it feels awkward (to her). It’s a problem. Should she affirm it or should she hide it? It’s shameful. It’s solid yet an empty space that nobody can enter. It’s isolated from the world. But in this uterus, there is a legendary phallus inside. It’s fragile but upright; it’s a lesbian phallus that only works for her woman. Ironically, this phallus is the only thing that connects the butch uterus to the world. Butch uterus opens up only for her woman. Ah, bu-chi-ei ja-gung” Audiences erupted in loud excited response. The shape of this audience member’s sculpture was a ball with a flower on top. Inside it was empty, but the flower was there to signify the hidden sexual nature of it. The statement written by this audience member reflected recent discourse around bu-chi appearing on social media. Today, bu-chi were hard to encounter, especially among younger members of the LGBTQ+ community. Bu-chi has become a historical figure nostalgically conjuring the queer past of the 2000s. Absent, the bu-chi can be idealized.

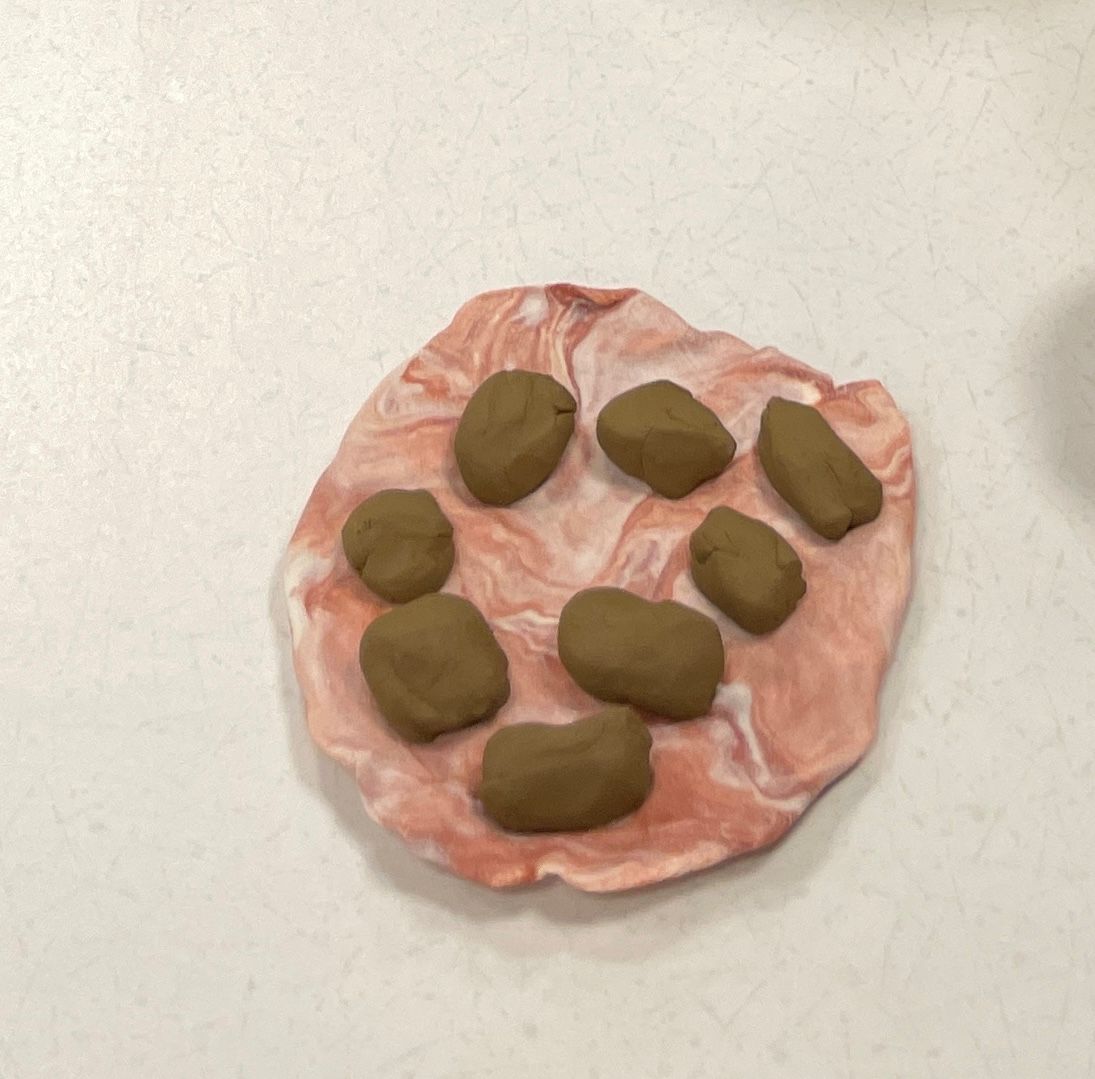

Another audience member shaped her butch uterus into multiple spheres, a sun and stones, and explained that she had remembered the dol-bu-chi (stone butch) while making her sculpture. She shared that she had completely forgotten about the stone butch for at least fifteen years until that very moment. This brought to everyone’s mind the many variations of the term bu-chi that used to be commonly used during the emergence of feminist youth culture and queer subcultures in the early 2000s, such as dol-bu-chi (stone butch), soft bu-chi, Ewha Woman’s University bu-chi, and so on.

As the workshop progressed, people began to share various queer affects still associated with the term bu-chi and their own attachments to them. The group discussion brought forth an unexpected sense of collective nostalgia and celebration.

On the other hand, discomfort also arose in response to the discussion of the butch uterus. When Ibanjiha asked people to explain the shapes they had given to their sculpted butch uteruses, one person said, “[The uterus] is a symbol of blood, but it dies if it’s taken out of the body. I think the uterus is just an excretory organ.” Ibanjiha answered, “I told you to shape a uterus but you performed a hysterectomy. […] You opened it up, and I see that shit is in there. Is this how you feel? There is only shit in there, no sons?” With this piece, the butch uterus had shifted from reproduction to excrement.

Furthermore, what was the notable among the audience was that no one had identified as bu-chi. They had all presented their pieces about bu-chi from the non-bu-chi point of view. They had imagined what a butch uterus might be or do but could not talk about their own bu-chi-ness or feelings about their own uteruses. During the roundtable discussion on the following day, Ibanjiha mentioned that the bu-chi presence was missing from the workshop. They speculated that discomfort or dysphoria around the body part might have kept some people from attending the event.

Ibanjiha then introduced two additional pieces that had not been displayed during the previous day. One seemed to be in the shape of an apple and the other in that of a dinosaur. Some audience members seemed not to have made anything clearly resembling the butch uterus. Why an apple, and why a dinosaur? Ibanjiha wondered aloud about the possibility of bu-chi folks not daring to join the workshop due to ambivalence or refusal to engage the uterus publicly. What did this refusal to appear mean for the workshop? What was the significance of evoking this absent presence? Who were the bu-chi and what were their experiences? Even though the workshop was purportedly about the butch uterus, there had been no opportunity to hear directly from a self-identifying bu-chi. Was this in fact where the workshop had been headed all along? Who were so-called ‘real’ bu-chi folk anyway? The reproductive organ that had proven to be laden with an excess of meaning ended with a dissolution of its own representability. Gathered around the topic of the butch uterus, the audience had made jokes and laughed at their own creations. The next day all of their handiwork were thrown away. In this tenuous space the uterus had temporarily detached from some of its heavy patriarchal values. In an imposing institutional space like the MMCA, a group of strangers had shared a moment of pleasure around queer art. They had talked about tabooed topics involving the queer body, sexuality, and secret affects, then dispersed.

1. 이반지하, 「부치의 자궁」, 『EPIIC』, 2022. 7. 4.

2. From here and onward, I use bu-chi, instead of the English term butch, in order to emphasize the Korean context of it. Bu-chi is not only a Korean pronunciation of the English term butch, but a translation/adaptation of the term in the lesbian community in South Korea. Korean lesbian communities have animated the term differently from the Anglophone culture. Bu-chi is never an adjective in Korean but a noun and ultimately, it is a personhood. Back in the 2000s, any member of the lesbian community was familiar with three categories: bu-chi, pem (originated from the English term femme), and jun-chun-hoo (the riversable). Bu-chi and pem had a variety of degrees, in accordance to where one locates themselves in the male-female spectrums. This genealogy of the terms is worth a further historical investigation.

Yeong Ran Kim is the Andrew W. Mellon Digital Media Fellow and an affiliated faculty member in Filmmaking and Moving Image Arts at Sarah Lawrence College. An interdisciplinary artist and researcher, Yeong Ran sees aesthetic practices as central means to build social movements that create unique moments of coming together. Yeong Ran's interdisciplinary projects draw together their research in the contemporary queer culture with performance theory, Asian/American studies, gender and sexuality studies, and film and new media studies. Yeong Ran holds a PhD from the Department of Theatre Arts and Performance Studies at Brown University.