platform_as_a_curatorial_research_lab_for_independent_curators

Chulayarnnon Siriphol, ANG48 (2022), still. Photo by Jutarat Ninnaihin. Photo Courtesy of the artist and Bangkok CityCity Gallery.

ANG48 - Why Is Decolonization and Internationalism So Challenging and Perplexing?

In the villages of northern Thailand, which border Myanmar, huge amounts of Japanese remains are scattered and buried. During World War II, Japanese troops tried to move through the Thai border to invade Burma, which was under British occupation. Soldiers were stationed in northern Thai villages, paving new roads or building bridges for smooth movement, and small northern villages provided goods and services to Japanese soldiers, and the economy was lively. Soon, the Japanese army was defeated, and thousands of Japanese soldiers died during the retreat, destroying even the bridges they had built. The Japanese remains, which began to be excavated in the late 1970s, are traces of this history. After the war, these areas, which were only rural villages in remote areas, became tourist destinations after the memories of the war were discovered, attracting people and revitalizing the local economy. Shrines honoring the souls of the fallen were built, and the war memory became a resource for Thai and Japanese tourists. This ironic memory of war history has also been transformed into a love story between a Japanese soldier and a Thai woman, and has become a folk legend. In Mae Hong Son, a city in northern Thailand, there is a shrine dedicated to a woman who became famous for the mochi rice cake recipe that a Japanese soldier with whom she had a relationship gave her, and her love story.

ANG48 (2022), a video by Chulayarnnon Siriphol, an artist who has been focusing on political issues and (post-)colonialism in Thailand through moving images and his own body, starts from this perplexing colonial relationship between Thailand and Japan. ANG48 is a recombinant and recreated video of his recent video works Golden Snail (2019), Golden Spiral (2018), and The Internationale (2018), which uniquely explores the history of colonialism and neo-colonialism between Japanese imperialism, Thailand and Asia. It explores all over the place with articulation methods, sharp satire and humor. The materials and territories of this exploration are popular cultures mediated by the media. The artist appropriates, articulates, twists, and parodies popular and transnational pop culture such as folk legends, beauty product advertisements disguised as expert opinions, melodrama films, and idol dances.

The beginning of the video is a montage of ruins, parks, sculptures, and archive photos, suggesting that these images are traces of war. What follows is a love story between a Japanese soldier and a Thai woman, which forms the axis of the video. The wall of the studio set where a woman is being interviewed becomes a screen and a video directed like a silent movie is shown. The video is regarded as a flashback paired with a voice-over of a woman doing an interview, but as it is presented in the form of a movie through the screen, it also seems to be a representation of the familiar public memory between Thailand and Japan after World War II. This silent film is a flashback of individualized memories and a representation of public memory about colonial relations, intertextually constructing each other's identity and memory between history and individuals.

Chulayarnnon Siriphol, ANG48 (2022), still. Photo by Jutarat Ninnaihin. Photo Courtesy of the artist and Bangkok CityCity Gallery.

A video in which a person who appears to be a doctor explains about exotic edible snails is inserted. It is said that giant snails brought from Africa to be raised for food while Japan built military bases in Southeast Asia reproduced at a frightening rate and spread throughout Southeast Asia. This video, which appears to be plausible information about snails, turns out to be an advertisement for snail essence cosmetics, which soon became a product of the beauty industry. And the woman in the cross-edited silent film gives birth to a giant snail that glows golden while fighting with a Japanese soldier. The giant snail's father, the Japanese soldier, leaves for his home country with the defeat, and the giant snail's mother misses him while making mochi with the recipe he taught. The snail girl born between Japan and Thailand and destined to become a market product is Angsumalin. Angsumalin is also the heroine of the popular novel Khu Kam (Thommayanti, 1969)1, which is familiar to Thai people enough to have been adapted nine times2, including movies, TV series, and musicals. Angsumalin is engaged to Banus, an elite Thai man studying abroad in England, but her heart is also shaken by Kobori, a young Japanese naval officer who is devoted and pure-hearted, who actively approaches her. Her father, a right-wing political leader, forced her to marry Kobori, but she couldn't even sort her mind with Banus. The artist synthesizes his own face with Angsumalin faces from films adapted from Khu Kam, which were adopted in the 1970s, 80s, 90s, and 2010s. The audience sees the artist's face attached to Angsumalin's body, which is shaken and torn between Banus and Kobori, Thailand and Japan. Angsumalin shows strong hostility to Kobori when she meets him because he is a foreigner, but their relationship soon turns into a friendly one. Angsumalin cannot decide her own destiny. It only confuses between Banus or father, and Kobori. By cross-editing newsreel and documentary footage documenting the boycott of Japanese goods led by the Thai government in the 1970s, and the reminiscences of her mother, who was unable to make or sell mochi anymore, the author cross-edited post-war right-wing nationalism and imperial Japan's colonialism which highlights the difficulties Angsumalin was facing not being able to do anything between them. This difficulty is repeated in recent Thai films throughout the ages and is also found in Taiwanese films that experienced Japanese colonial history.

Confessing the irony of her birth in Japanese, Angsumalin makes copies into dozens of bodies and heads for space. In space, can the ironies and difficulties derived from colonialism and post-war nationalism reduce? Can Angsumalin be completely free between the boundaries of history? Drenched in giant snail juice, Angsumalin becomes an idol dancing in a sailor uniform. Just like the fertility of giant snails spreading across Southeast Asia at an alarming rate, marketization and commercialization break down all boundaries and unite us all. The most powerful force that unites everyone while expanding their territory as vigorously as the giant snail is now is the song and dance of idols. The 48 idol groups in Tokyo, Osaka, Shanghai, Jakarta, and Bangkok exist everywhere in a different way from imperialism, which used force while singing — or selling — love, friendship, and courage. From the beginning of the 20th century, the National Socialist movement, the radical leftist movement in Europe, North America, and Japan, and the democracy movement in the Third World all shouted and sang together, but the ‘The Internationale’, which could not be realized, finally lifted the body of Angsumalin in a sailor suit and realized through. Is it realized? The artist doubts and disturbs ‘The Internationale’ realized at the same time by inserting images of statues of girls from various parts of Asia and a performance video in which Angsumalin wears a sailor suit and visits a shrine dedicated to the love between the Japanese soldier and a Thai woman and offers homemade mochi. The editing and arrangement of the two-channel video further intensifies the disturbance by mixing and synchronizing their order. Here's the sobering reality. Half of Angsumalin came from Japan. Since modern times, our daily lives and perceptions have been composed of colonialism and imperialism. No one is free from this perplexing cul-de-sac. Like the spiral pattern on the shell of a giant snail, it repeats endlessly in a spiral like the spiral staircase of the Bangkok Art Center, modeled after the Guggenheim in New York. This is the core of the criticality of Chulayarnnon Siriphol's work, which connects colonialism, which still leads to market domination through popular culture, with his own historical genealogy, and expresses himself by dividing and fragmenting his body.

Mooni Perry, Binlang Xishi (2021-22), still.

Mapping with Mooni Perry: Genre Yuri or GL (Girls' Love) - Radical Queerness in GL

After watching the film The People of the Ataka Family (directed by Seiji Hisamatsu, 1952) starring Kinuyo Tanaka, which was based on a novel by Nobuko Yoshiya, I struggled to find other films based on novels by the same author for a while. The People of the Ataka Family is one of the tendencies of Japanese films produced during the post-war allied occupation period after the defeat, the fall of the old era (symbolized by damaged patriarchy, old capital, and old class) and the new era (represented by women and the public) which can be seen as a movie about a lonely prelude, but what caught attention most of all was the relationship between the women in the movie. Kuniko, who has situated a unique position within the Ataka household as a caretaker for her disabled husband, a manager of the household's affairs akin to her father who was a butler, and a mediator between the employees and the family, finds solace and support in her interactions with Masako, the wife of her husband's brother, as they navigate the intricacies of their familial dynamics and societal expectations. Ultimately, both women make the bold decision to break away from their traditional roles and dissolve their family ties, opting instead to relinquish their inherited wealth and power to the masses. The story and the ending of the film invites the (female) audience to reconstruct the movie as a secret solidarity of women through the lens of the film The People of the Atakas. The original author, Nobuko Yoshiya, began submitting novels with girls as the main characters to magazines from the early 1900s when she was a teenager, and continued to write novels about women until her later years in the 1970s. The Flower Stories (Hanamonogatari) series, which has been made into several films as well, is a series of short stories that depict the psychology and relationships of girls with different flowers3, for about 10 years, it was serialized in two magazines with enthusiastic support from the girls of the time. In particular, in the latter half of the series, as the stories of featuring strong ties between girls and homosexual themes became more prevalent and resonated with readers,, it is considered the origin and start of the genre known as Yuri that has seen a resurgence in popularity since the 1970s. ‘Girls’ schools’, which are based on a conservative and patriarchal culture of gender separation,, allow female students to reflect on themselves and form relationships outside of heterosexual norms.4 Nobuko Yoshiya's The Women's Classroom (1939), which has been made into films and stage plays several times, is set during the Sino-Japanese War. Although the title The Women in the Rear Guard was created to emphasizes the responsibility and duty of women in the rear on behalf of men drafted for war5 to reorganize women, the women in the rear guard focuses on identity, self-reliance, and relationships between women as independent individuals, separated from men or husbands, in the context of time and space without men.

Mooni Perry's previous works, which combine video, installation, and performance, Binlang Xishi (2021–22) and Missing (2022–) show the ambivalence of culture occupied by women — as inferior beings in the patriarchal order — or others associated with women, and explores radical possibilities through its appropriation and parody. The combination of the status and sexuality of women selling betel nut in Binlang Xishi brings the image to the fore, so that the women selling betel nut (binlang) rather play and perform the existing image in full. By bringing the concept of dirt and inferiority to the fore, it makes the separation of ‘dirty’ and ‘clean’ unfamiliar, rather than accepting the existing image, and makes us ask questions and deconstructive questions about the process of the separation being rescued. Missing borrows and mixes the frame of reverse harem and the layout design of role playing games in female subcultures including same-sex/interspecies romance, detective stories from popular narratives, time travel genre and popular movie subplots based on Chinese tales, and animation which conducts a critique of radical ecofeminist positions on anthropocentrism and interspecies inequality. According to Judith Butler, the process of receiving, appropriating, and accepting norms is the process by which the subject, that is, the speaking “I” is formed.6 ‘I’ cannot help but be formed within the existing norms, and the possibility of having other performativity by actively appropriating the norms also comes from this process of appropriation. Butler speaks of appropriation moving between rejection and absorption of existing norms: “Antigone's autonomy is achieved through the appropriation of the voice of authority of the person she stands against, an appropriation that bears within herself both the rejection and the absorption of that very authority.”7 Judith Butler responded to discussions criticizing the performance of New York ball culture in the 1990s that borrowed existing heterosexual norms or appropriated the gender role of heterosexual relationships and the conservatism of the desires of gays, lesbians, transgenders, and drag queens who participated in it: “In other words, after all, the drag queen, molded for us and filmed for us, is a figure who both appropriates and subverts racist, misogynistic and homophobic norms of oppression. But how can we explain this ambivalence?

Mooni Perry, Mapping with Mooni Perry: Genre Yuri or GL (Girls' Love) (2022), still.

This ambivalence is not the kind of ambivalence that first appears as appropriation and later as subversion. Sometimes the two appear simultaneously, sometimes such ambivalence is caught in an insoluble tension, and sometimes fatally a nonsubversive appropriation takes place.” We cannot, by fate, say what is radical or conservative. It is to create radical moments and actions while questioning how they are composed within the repetition, arrangement, and rearrangement of performance within and outside the network of semantics and relationships of norms. In Mooni Perry's works, the genre frameworks of popular culture and subculture, which are familiar and cannot be called critical or radical in themselves, are appropriated and parodied, allowing us to look into existing powers and at the same time construct new semantic networks.

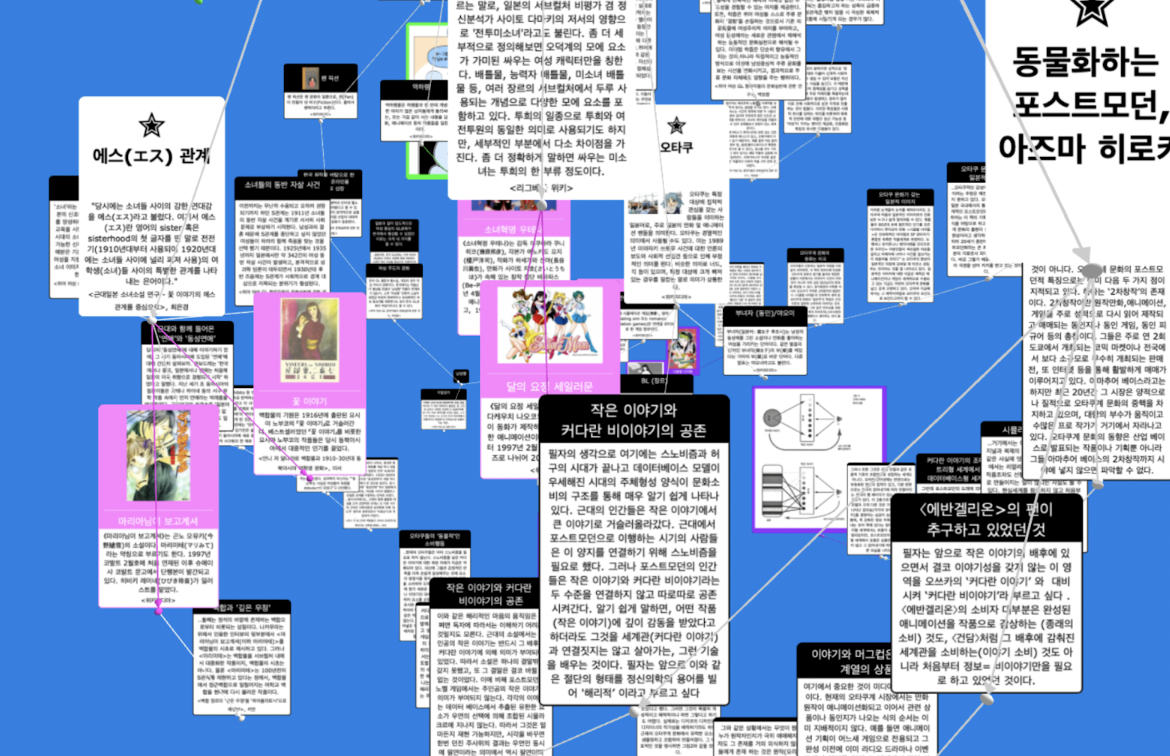

Mooni Perry's new work Mapping with Mooni Perry: Genre Yuri or GL (Girls' Love) explores the female-only subculture of yuri or GL. More precisely, it explores the queer radicality of GL. Showing the methodology of appropriating the images and frames of existing popular culture and subculture through a 3D map as a collage of text, literally mapping, drawing a map itself is the core of this work. This map begins with Yoshiya Nobuko's Flower Stories (Hanamonogatari) and discusses the characteristics of a contemporary subculture in which consumers and producers are not separated and the form of ‘consumption’ becomes more important, and the ‘Omegaverse’ becomes more important, and worldview, which can be seen as the most recently observed form of imagination in relation to gender, sexuality, and women. Vertically and horizontally, it leads to a cross-cultural study of regional, post-colonial, and postmodern capitalist contemporaneity, the differences and commonalities between GL, queer works, and BL, and the United States and Japan. However, this map is not simply a commentary on GL culture. It is a work to dismantle the monopoly status of heterosexual romantic love since modern times and to engrave the genealogy of relationships between women in the history of construction of modernity, plus an attempt to feminize modern queer history. In addition, BL and GL, which have a commonality of a culture almost exclusively occupied by women, are contrasted, focusing on the distance between the character (s) in the work and the creator/enjoyer, and the party. In this mapping of Mooni Perry, GL is positioned as a text that has a direct and deep relationship with women's reality, and as a mutually constructive text in which women create their own ‘party’.

While having a relationship with the reality of GL, Mooni Perry, who vigorously explored non-normative and fluid radicality, attaches the modern otaku culture that has built a closed, self-sufficient, and consuming world that is increasingly disconnected from reality, as discussed in Animalizing Postmodern by Azuma Hiroki. This montage or collage looks somewhat different from the development of the previous mapping. When the previous map drawing was a chronological yet organic flow that converges into one point, female homosexual culture and GL creation/enjoyment from the early modern times to recent subcultures in Korea, this ‘animalized postmodern’ otaku culture is separated from reality and buried in the self-sufficient genre culture itself, and in a broad sense, it is identified and subsumed as neoliberal consumption. What's the problem when these collages collide? Is this ‘animalizing postmodern’ otaku culture critically emerging in contrast to current GL culture, or is it a part of the development of GL culture that Mooni Perry is concerned about while mapping? The otaku culture that Azuma Hiroki discusses is distinct from the GL culture discussed in Mapping with Mooni Perry: Genre Yuri or GL (Girls' Love) in that it is a male-centered culture for both creators and enjoyers, and that it is a reality glass with closure. However, the effect of the structure of this mapping, which consists of collisions of quotations and texts without any other explanation of the connection, seems to be both a privilege of GL and a concern for the future. After building the radicality of GL culture centering on the dismantling of heterosexual culture, the feminization of queer history, and the party that is distinct from BL, Azuma Hiroki was added, and while emphasizing the uniqueness of GL culture, it manages to add the ambivalence of concern about future developments.

As women build and reciprocally rebuild their identities, GL culture has secretly expanded its radical imagination. The discovery of the imagination of GL culture, which starts from familiar relationships but is not returned anywhere, and the ambivalent position of expectations and concerns about unpredictable future developments reminds Chizuko Ueno's discussion of girls' school culture. As women build and reciprocally rebuild their identities, GL culture has secretly expanded its radical imagination. Mooni Perry articulates and connects the imagination of GL culture, which originates from familiar relationships but is not returned anywhere, to feminist science fiction. This article ends with a sentence about the unknown future brought by Chizuko Ueno's 'Girls' School Culture'. “In the world of media, the girls’ school culture is expanding its territory deeply and widely. … What will happen when this dark continent, which has been a blind spot for men, suddenly appears in front of their eyes, just as the fantasy Atlantis sometimes rises from the sea?”8

1. The TV series aired in 1990 recorded the highest ratings ever in Thai broadcasting history.

2. Serialized in Sri Siam magazine in 1965, first volume published in 1969.

3. 3 films were made into films, among which 2 films of the same name (1935) adapted from Buttercup Flower and Flower Diary (1939) adapted from Bellflower remains as a film due to efforts such as the discovery of NFAJ (formerly NFC). Buttercup Flower depicts the homosexual relationship of girls, and was screened at the 18th Tokyo International Lesbian & Gay Film Festival immediately after the discovery and restoration of NFC. https://rainbowreeltokyo.com/2009/program/pre/01_fukujyusou.html

4. Of course, none of these relationships are morally right or good, and they all have their downsides. Nevertheless, it is radical in that it builds something new in a place different from the male or heterosexual patriarchal point of view. The deepening of this discussion can be referred to in “Chapter 11 Girls' School Culture and Misogyny” in Chizuko Ueno's book Hate Misogyny (Onna Girai -Nippon No Misogyn).

5. It is a discourse that reorganizes the identity of women in the rear as war-related under wartime by emphasizing the role of women who did not participate in the war under the total mobilization system during the Japanese imperialist war in rear management, education, and mobilization of materials. Kwon Myeongah, The Women in the Rear Guard, New Woman, and Spy, Sang-heo-hak-bo, 2004, vol.12, pp. 251-282.

6. Butler discusses this in several books, but in particular, she discusses it intensively in Hate Speech (Ryu Min-seok, Aleph publishing) and Gender Demolition (Cho Hyun-jun, Moonji Publishing Co., Ltd.).

7. Judith Butler, Undoing Gender, pp. 267.

8. Chizuko Ueno, Hate Misogyny (Onna Girai -Nippon No Misogyn), pp. 212.

Hwang Miyojo is a feminist film researcher who has studied film theory, cultural studies, East Asian studies, and comparative literature. She teaches feminist film criticism and East Asian film studies at Korea National University of Arts and works as a programmer for the Seoul International Women's Film Festival and the Seoul Animal Film Festival.